I’ve been working in county courthouses since 2013, usually alone, sometimes with a student assistant or two. By now, I take for granted that the work will be dusty, too cold or way too hot, and maybe filthy. I expect to be directly under pipes through which I’ll hear every toilet flush in the building. I’m not surprised when lights flicker and ducts hum and tick. I know that there will be few places to sit and few flat surfaces on which to read documents, write notes, or set up a laptop. I’m sure my neck will hurt when I leave that day.

After doing research in five courthouses in Virginia and North Carolina this month, I came to see that these work spaces are not native to central Pennsylvania. The backroom in a clerk of court office is of a standard type. Here’s my view during six hours of scouring circuit court judgment and order books in Halifax, NC:

During that time I heard the distant conversation of employees: what foods they wanted to try, what movies they had seen, how they were going to spend their weekend. I saw people through the doorway as they pulled files, made copies, or passed through the outer office. But no one ever came into this 10′ x 20′ closet filled with old desk lamps, mid-twentieth-century file cabinets, and swivel chairs that just barely swiveled. It was just me and the hundreds of people indicted for liquor law violations in Weldon or Scotland Neck during Prohibition.

They all pretty much look like that. The rooms in Bedford and Campbell Counties were larger, to be sure, with multiple aisles and better lighting. The space in the Charlotte County had been partially renovated, with new drywall meeting old cinder block. The record room of the Lunenburg County Courthouse has more windows and sociable clerk of court at a nearby desk. But they all convey the feeling that the important work in the building happens elsewhere.

The bulk of the research that’s built the projects on this site has been done in the Northumberland County Courthouse (NCC) in Sunbury, PA. It’s 20 minutes from my campus and has a staggering amount of trial transcripts from the 1920s and 1930s. Transcripts are the great lost treasure of courthouses, because they take the researcher closer to the messy, quaint, hidden details of everyday life in the past. The human stories behind court cases come through in transcripts in a way they don’t in the courts’ other paperwork. The NCC has hundreds of original transcripts. It’s where students and I have taken at least 20,000 photos of more than 100 cases involving car accidents, divorce proceedings, and insanity inquiries.

What’s great about the NCC is that so many of its records are chaotically strewn throughout file cabinets and cardboard boxes in the original cells of the county jail. Boxes sometimes bear titles written with marker, scratched out, and rewritten. But box titles often have little to do with what’s inside. With permission from the county commissioners, one can browse massive amounts of material that are only loosely organized. If you, the researcher, are organized, you can just about keep track of your progress in these spaces, making notes to yourself like “start next time under the box that says “Georgia-Pacific Paper” or “start with the stack on top of the red corner cabinet labeled Superior Court.” You might take selfies pointing to where you left off in a sea of boxes and drawers.

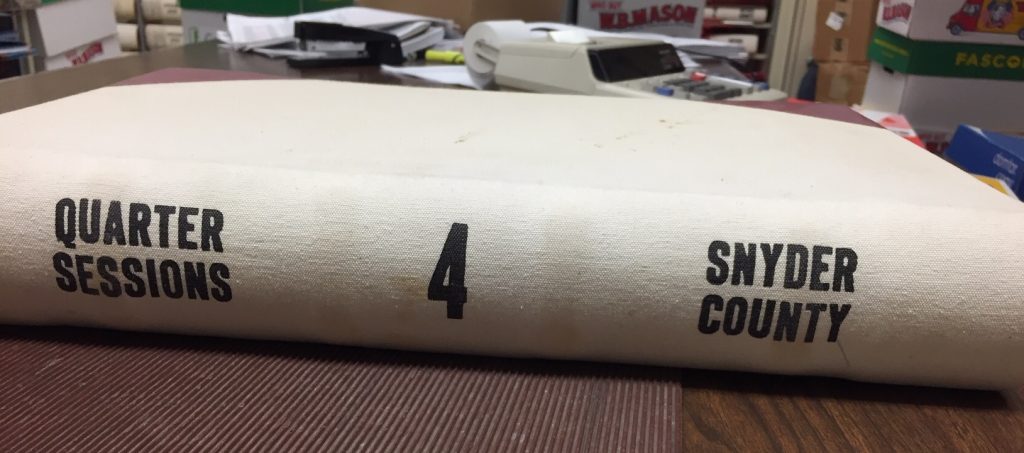

Making true discoveries, though time-consuming, is possible at the NCC. That’s rare. Most courthouses no longer contain these records; they were “purged” decades ago when space became an issue or they’re locked away in storage and aren’t publicly accessible—because no one with whom a researcher might interact has any idea they’re there. When the purges happen, it typically means that some records have been sent to the state archives. But some are certainly destroyed after being deemed as without any kind of historical or institutional value. The vast majority of courthouse research for the early twentieth century thus takes place via volumes like this:

Using such volumes necessitates a bulk approach, in which you focus more on patterns in the data than on any individual stories. So researching in a courthouse that has only bound volumes of court proceedings turns into a race to get as much documented as possible before your eyes start to hurt, your phone is full, or the building’s about to close. The work of interpreting and analyzing happens later, after photos have been turned into Word files or spreadsheets.

But places where there are more “granular” sources offer different paths. The Snyder County Courthouse (SCC) has the typical bound volumes of court proceedings in its records room, but it also contains the far more interesting “room 007” in the basement. With a locked door, exposed pipes, and months’ worth of stored toilet paper, room 007 holds useful, seemingly forgotten sources. That’s where to find the county’s “lunacy papers,” its liquor license applications after the repeal of Prohibition, its dog license records from the 1920s, and its gasoline tax records before the 1940s. With some imagination, the minutiae of the past becomes narratives of how people lived, what they cared about, and how they treated each other.

Working in these spaces makes you appreciate the tidy and monitored reading rooms that many archives and special collections libraries maintain. Yet there’s a lot to be said for the feeling that you’re perusing documents that no one has looked at for a long time, and that you might be able to bring them back to life by finding the value in them—and telling others.