I’ve always thought that hearing an author read their writing out loud is the best way to understand the work. That’s why slam poetry has always had a tight hold on me, and how it has earned a prioritized place in my heart. Authors can combine the beauty and technique behind language with live performances in a way similar to song, but also different. Song has a specific structure, involving verses, a chorus, and a bridge. However, poetry is to wide a genre to have such restraints, so even if a slam poet adds music to their performance, it doesn’t turn their poem into a song. It’s just a poem to music.

There are countless channels of media that house slam poetry, the most popular and easily accessible being found on the internet, especially YouTube. Slam poetry circulates quickly and easily. Public places like coffee shops, high schools, and universities host open mic nights all the time. If even just one person records a performance, it has the potential to go viral on social media, since that person has the ability to make that content available for everyone to access by posting it on FaceBook, YouTube, Twitter, Tumblr, etc.

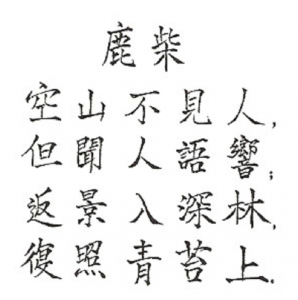

Because slam poetry is both spoken and written, it’s only barrier is that of language. Even though we can translate poems, the true meaning and message won’t always transfer properly. In fact, most of the time translations vary and can be easily skewed. For example, despite not being slam poetry, Wang Wei’s 1200-year-old four line poem, “Lù zhái”, or “Deer Park” (even the title’s translation is unclear), has been translated countless times from it’s original Chinese into many languages, back and forth.

In one of my poetry classes last year, we look at the book 19 Ways of Looking at Wang Wei, by Eliot Weinberger and Octavio Paz. It visualizes several translations that are all extremely different to demonstrate the power of language, translation, and interpretation. Chinese is especially interesting, because it is a tonal language. Just like English, it has a certain, distinguishable rhythm when spoken as opposed to read, but there are many words that, in Chinese, would mean the same thing if they were not pronounced in different tones. For example, the characters 马 and 吗 look very different, but the words, “mǎ” (tone 3) and “mā” (tone 2 ), mean horse and mother, respectively. As you can see, spoken quality is important, and that brings around my stress of the importance of slam poetry.

), mean horse and mother, respectively. As you can see, spoken quality is important, and that brings around my stress of the importance of slam poetry.

Slam poetry is literature spread by way of sound. Despite sounding super meta, it began in 1984, in Chicago. Though, back then, YouTube and FaceBook didn’t exist, and therefore, sharing was limited to the witnessing of live performances. It’s truly incredible what technology has done for the industry, by allowing slam to be spread and circulated widely. Because it can be applied to so many different platforms due to it’s auditory nature, slam is easy to produce, and moves across many forms and channels of media easily.

Word Count: 499

Works Cited:

Ovitt, George, and Peter Adam Nash. “Talented Reader: a Literary Journal.” The Art of Interpretation: “Lu Zhai” or “Deer Park” by Wang Wei, 1 Jan. 1970.

“Poetry Slam.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 21 Mar. 2018

Weinberger, Eliot, et al. Nineteen Ways of Looking at Wang Wei: How a Chinese Poem Is Translated. Asphodel, 1987.